Prediction, Understanding, and the Discomfort Beneath the AI Debate

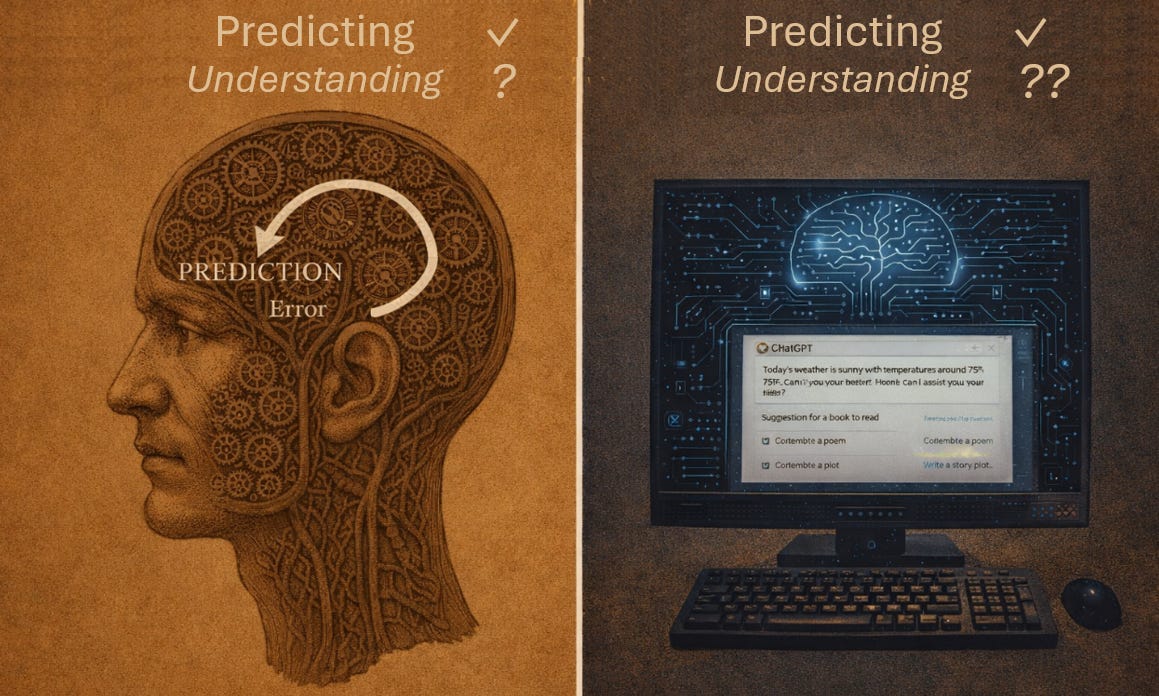

In a recent blog post, Artificial Intelligence and Education: What Will Change — and What Will Not, Dylan Wiliam makes an important and timely point about generative AI systems. Models such as large language models, he argues, do not “understand” in a human sense; rather, they predict plausible continuations of input. Appreciating this distinction, he suggests, is essential if we are to avoid both inflated expectations and misplaced fears about AI in education.

At face value, this claim is uncontroversial. Current AI systems are, in a clear and technical sense, prediction engines. They generate outputs by modelling statistical regularities in vast datasets, not by grasping meaning in any rich or human way. However, when we examine what human understanding actually consists of, the contrast between “mere prediction” and “real understanding” begins to look less clear, and perhaps less helpful.

A different way of thinking about human cognition

If you have been following my previous blogs, you will know that I take a particular view of human cognition. Rather than seeing the brain primarily through traditional information-processing models that still dominate much educational thinking, I see human cognitive architecture as fundamentally predictive. This view reflects developments in contemporary neuroscience and cognitive science, where Predictive Processing and Active Inference have become increasingly influential frameworks for explaining perception, action, learning, and decision-making.

On this account, the human brain is not a passive receiver of information. It is an active generator of predictions about what is likely to happen next. Perception, learning, and decision-making are all organised around reducing surprise by improving those predictions over time.

What we really mean by “understanding”

From this perspective, human understanding is not privileged access to how things truly are. It is the possession of a sufficiently good generative model to predict how similar situations are likely to unfold in the future. When we say someone understands a concept, a phenomenon, or a problem, what we usually mean is that they can anticipate outcomes, explain patterns, and act effectively across relevant contexts.

Understanding, in other words, is pragmatic rather than metaphysical.

Crucially, this means that human understanding is not optimised for truth in any absolute sense. Our models are shaped by evolutionary pressures to be useful, efficient, and good enough for survival. They may simplify, distort, or ignore aspects of reality that do not matter for action. Even our most successful abstractions, including scientific theories, are best understood as increasingly powerful predictive compressions, not final descriptions of how the world really is.

Seen in this light, the claim that AI systems “only” predict plausible continuations begins to look less like a decisive limitation and more like a shared foundation. If understanding consists in having a generative model that supports reliable future-oriented prediction, then the relevant question is not whether AI predicts, but how well it predicts, across what domains, and under what constraints.

Why AI prediction still falls short

This is where recent work by Giovanni Pezzulo, Thomas Parr, Paul Cisek, Andy Clark, and Karl Friston is particularly helpful. In their 2024 paper Generating meaning: active inference and the scope and limits of passive AI, the authors explicitly acknowledge that both biological cognition and modern generative AI rely on generative models and prediction. The overlap is real and important.

However, they argue that the way those models are acquired and used differs in ways that matter for understanding.

Current large language models learn primarily through passive exposure to curated data, predicting tokens from tokens. By contrast, biological systems learn through purposive, embodied interaction with the world. Their predictions are continually tested and refined through action, where what the organism does changes what it senses, and where survival-relevant needs shape what counts as salient.

On an Active Inference view, meaning and understanding arise from models that predict and control the consequences of action. Objects, concepts, and explanations matter because they specify affordances: what can be done, and what is likely to follow if one acts. This continual loop of action, consequence, and correction gives human predictions a depth and robustness that current AI systems lack.

Importantly, Pezzulo and colleagues do not claim that AI prediction is categorically different from human cognition. Nor do they appeal to anything magical or non-computational. Their argument is more precise: prediction becomes understanding when it is grounded in action, consequence, and stakes. Without that grounding, predictions may be fluent and impressive, but they remain fragile, brittle, and prone to failure outside the conditions they were trained on.

A brief note on consciousness

A related but distinct issue that often becomes entangled in these discussions is consciousness. Whether an intelligent system is conscious, has a sense of self, or possesses subjective experience is a separate question from whether it can build generative models that support accurate prediction and effective action. Within Predictive Processing and Active Inference, many authors have argued that consciousness and the sense of agency can be understood as emergent properties of certain kinds of self-modelling predictive systems, rather than as prerequisites for intelligence or understanding. This literature is extensive and ongoing, but it is not the focus here. The key point is simply that debates about understanding should not be settled by appeals to consciousness.

The deeper source of discomfort

The deeper discomfort in debates about AI understanding, I would argue, lies elsewhere. It is not that machines might be “only” predicting, but that humans are too.

Once we take Predictive Processing seriously, several intuitions quietly fall away. Our explanations are not windows onto underlying reality; they are outputs of our generative models, constructed because they help stabilise prediction across time and context. When we explain why something happened, we are not uncovering an essence. We are generating a narrative that compresses past experience and supports future expectation.

Even the feeling of insight, of “really getting it”, can be understood as part of the brain’s self-model. It signals that prediction error has dropped to an acceptable level. It does not guarantee that the model is true, only that it is currently useful. From this perspective, explanations themselves are a special class of predictions, valued because they help coordinate future action and belief.

Recent work by Sebastian Barros (2025) further sharpens this picture by addressing a common objection to predictive accounts of intelligence: hallucination. Barros argues that hallucinations in both humans and large language models arise from the same underlying mechanism—prediction under uncertainty. When sensory input or data are incomplete, predictive systems fill in gaps with their best guesses. In humans, this produces illusions, false memories, and confabulated explanations; in AI systems, it produces fluent but incorrect outputs. Importantly, the paper argues that this is not a defect unique to artificial systems but an inherent trade-off of intelligence itself. A system that never hallucinates is one that never infers, imagines, or generalises. From this perspective, human misconceptions can be understood as locally successful hallucinations—predictions that have not yet encountered sufficient corrective feedback. What distinguishes current AI systems is not that they hallucinate, but that they lack the rich, action-based and metacognitive mechanisms that routinely regulate and correct human predictive errors.

Conclusion: prediction, all the way down

None of this implies that current AI systems understand in the same way humans do, nor that they should replace human judgement in education. Dylan Wiliam is surely right to emphasise the enduring importance of judgement, adaptability, and learning how to learn. But it does suggest that we should be careful about grounding those claims in a sharp opposition between “mere prediction” and “real understanding”.

The real challenge posed by AI may not be that machines are too simple, but that humans are less metaphysically special than we assumed. Our richest forms of understanding, including our explanations of why things happen, may turn out to be nothing more, and nothing less, than highly successful predictions about what comes next.

Recognising that does not diminish education or human intelligence. It clarifies what they are, and what we should genuinely value, in an age of increasingly powerful predictive systems.

REFERENCES

Barros, S. (2025). I think, therefore I hallucinate: Minds, machines, and the art of being wrong. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05806.

Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.05806

Pezzulo, G., Parr, T., Cisek, P., Clark, A., & Friston, K. (2024). Generating meaning: active inference and the scope and limits of passive AI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 28(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.10.002

Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661323002607